Glossary

Glossary

Methodology: An indicator framework to track EU progress to climate neutrality

Building blocks of a climate neutral economy and society

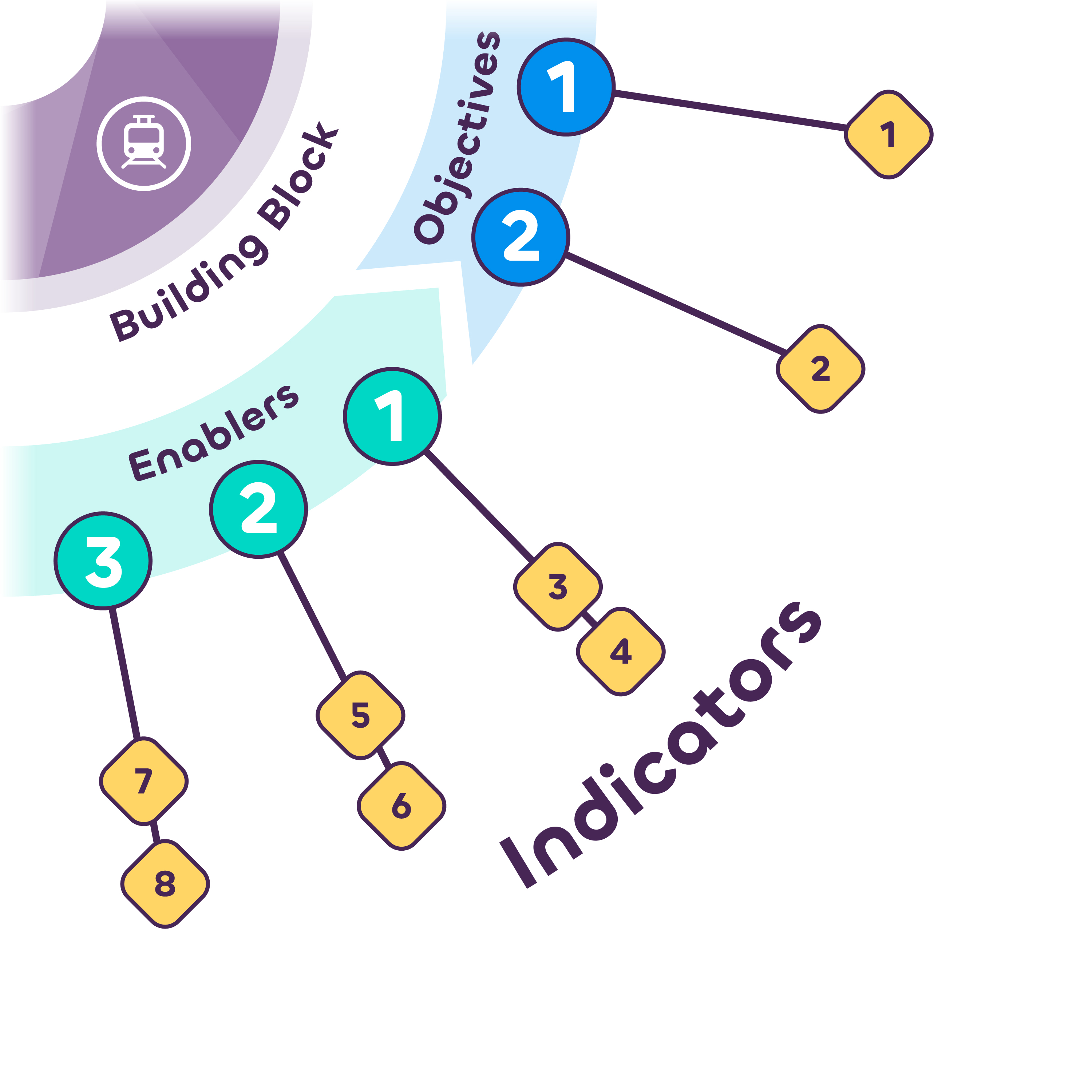

ECNO uses an indicator-based framework that tracks progress across traditional economic sectors (electricity, industry, etc.) as well as the cross-cutting areas that have an impact on the emitting sectors, like finance, governance, and lifestyles. Together these form the ‘building blocks’ of a climate neutral future.

Sectoral

Electricity powers modern societies, and its importance will only increase over time with the electrification of demand sectors. Renewable energies and their integration into the system are crucial.

Mobility connects people and sustains economies. For a transformative shift, reducing motorised transport, promoting clean modes, and decarbonising remaining transport are essential.

The EU needs a globally competitive and sustainable industry for economic prosperity and security. Cutting emissions in industry will depend on availability of zero-carbon energy and feedstock carriers and infrastructure, circularity, and energy efficiency.

Buildings facilitate activities essential for human life and society. Optimising building services, renovating them, and transitioning to renewable technologies are crucial.

Agrifood refers to all stages of the agricultural supply chain, from food production to consumption to disposal, while also considering aspects of land use and the production of agricultural inputs.

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is crucial to compensate for minimal residual emissions. It requires storing carbon in trees and soils and potentially using sustainable technical solutions in the future.

Cross-cutting

Sustainable behaviour patterns and social practices, enabled by policies that make sustainable options accessible, affordable, and the default, are key for decarbonisation.

Clean technologies are the backbone of a decarbonised economy. It is vital to deploy the most effective climate solutions, and that citizens reap the benefits of green industrialisation.

Redirecting financial flows towards the transition is essential to put the EU on track to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. This includes both public and private investment flows.

Just transition refers to designing and executing the shift to climate neutrality in a fair and inclusive way. Job opportunities, regional policies, and managing distributional effects are essential to the process.

Governance refers to the institutions, procedures, and frameworks used by governments to manage and guide policy-making and foster societal buy-in for the transition to climate neutrality.

Climate adaptation is necessary to respond to unavoidable climate impacts. It requires implementing effective adaptation measures on the ground as well as supportive governance and financial frameworks.

Addressing climate change requires a collective global approach. It is key for the EU to consider the extraterritorial impacts of its actions, prioritise climate diplomacy and support other nations in decarbonisation efforts.

Objectives

For each building block ECNO defines an overarching objective. Objectives outline what the building block must achieve to support climate neutrality.

All sectoral building blocks include the respective GHG emission reductions as one of the objectives.

Enablers

Enablers are the underlying real-world or structural conditions that support each building block in realising its objectives en route to climate neutrality.

Enablers are a core innovative part of ECNO's analytical approach. By looking at the underlying systems that support (or hinder) emission reductions, we can get an early sense of progress - or lack thereof - and where future bottlenecks might arise.

Enablers tend to function in one of three ways: (1) removing climate-damaging activities such as excessive fertiliser use (agrifood); (2) shifting attitudes, consumption patterns, or business practices like the uptake of zero emission and low carbon transport (mobility); or (3) improving existing systems, such as adopting robust institutional arrangements to ensure coherent policy-making (governance).

Indicators

The assessment of progress for each building block towards its objectives and enablers is based on indicators. These indicators describe specific aspects of the objectives and enablers and offer a view on past changes in the context of the required future changes.

Indicators were chosen to provide a comprehensive picture of progress for each building block. The ECNO indicator set includes both commonly used indicators as well as ones that go beyond the standard approaches to produce new insights. This is particularly the case for the cross-cutting building blocks where quantitative analysis is limited and policy goals are either non-existent or qualitative in nature.

For some indicators, data availability is a significant challenge. Although having a good data basis is crucial, this limitation did not restrict indicator selection, especially in those cases where there was no second-best indicator or proxy found. These cases point to areas where new data gathering and indicator creation activities, as well as new monitoring and reporting obligations, may be recommended to inform policy-making.

Assessing progress

Based on data over a past time period, indicators show the historical development of the objectives and enablers and allow for a comparison of a past trend with the required change. However, what is meant by ‘required change’ depends on a vision of each indicator’s contribution to climate neutrality.

Benchmarks

Benchmarks are future reference points against which progress for each indicator is compared. ECNO derives benchmarks from official EU sources, such as directives, regulations, strategies, or action plans, including their related impact assessments. Benchmarks often come in the form of quantified policy goals or targets.

ECNO applies the EU’s own vision of climate neutrality

Many of the indicator benchmarks were found in the impact assessments accompanying the EU 2030 Climate Target Plan and the EU long-term strategy (EU LTS). Importantly, not all indicators have benchmarks and for these a slightly different approach for assessing progress is taken.

ECNO compiles data from official sources as well as a range of open-source databases and research conducted by members of the ECNO consortium. This includes, but is not limited to, statistics from Member States harmonised and provided by Eurostat or the European Environment Agency (EEA) as well as from international organisations such as the OECD, FAO or World Bank.

Indicator data is collected over the most recent past period of five years for which data is available, such as between 2017 and 2022. This approach focuses the assessment on the latest developments and attenuates the influence of outliers

While data on headline indicators, such as GHG emissions or renewable energy shares, are readily accessible, limited and less regular or continuous information is collected for the structural changes that enable the transition. A significant challenge to an assessment of detailed progress is therefore the availability of data. Where this limits the interpretation of results, ECNO highlights critical information gaps.

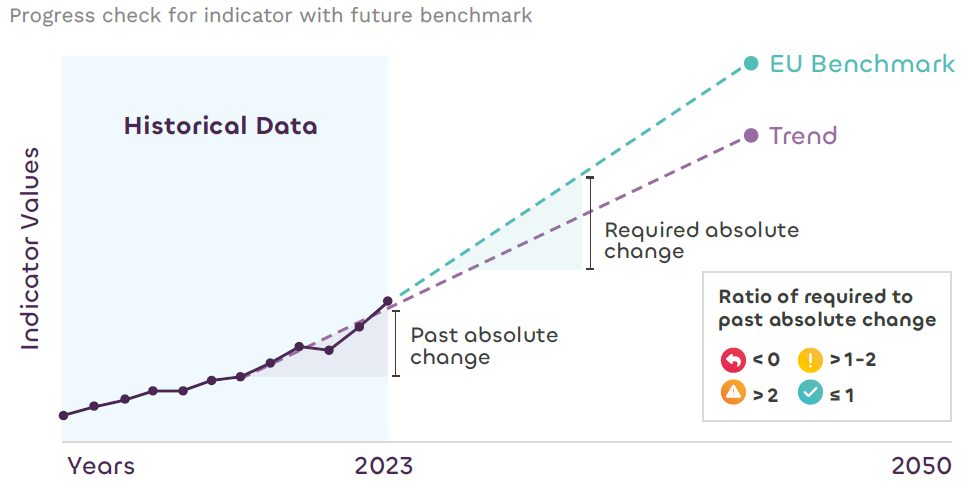

Indicators with a benchmark

The progress check for indicators with a benchmark compares the absolute annual change of the past development with the required absolute annual change to meet the future benchmark starting with the last data point of the trendline and drawing a straight line to the benchmark. The ratio between these two values indicates the required change in the pace of development or the acceleration factor.

The change that would describe a pathway that meets the identified benchmark. Where benchmarks are missing, the required change indicates the desired direction and speed of change.

The development of an indicator based on historical data. ECNO’s trendline is a straight, best-fit line that smooths out the variation in historical development based on all data points, providing a sense of the general progress over time.

The ratio between the absolute past change and absolute required change indicates the necessary absolute change in the speed of progress. This only applies for indicators with a benchmark.

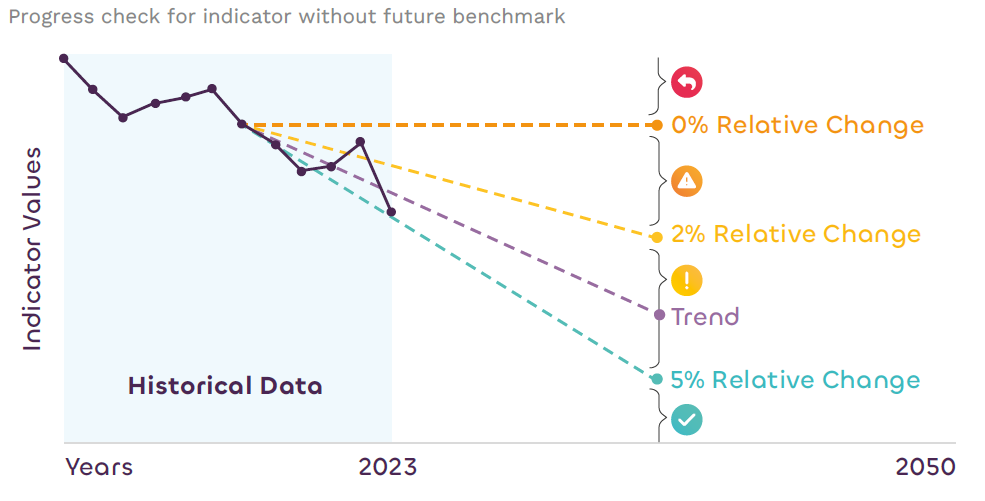

Indicators without a benchmark

If no quantified future benchmark can be derived from EU sources, the analysis relies on qualitative insights from official EU documents as well as on external scientific literature outlining the desired direction and pace of change. Therefore, the analysis also considers non-official EU benchmarks and expert judgement to put past development into perspective.

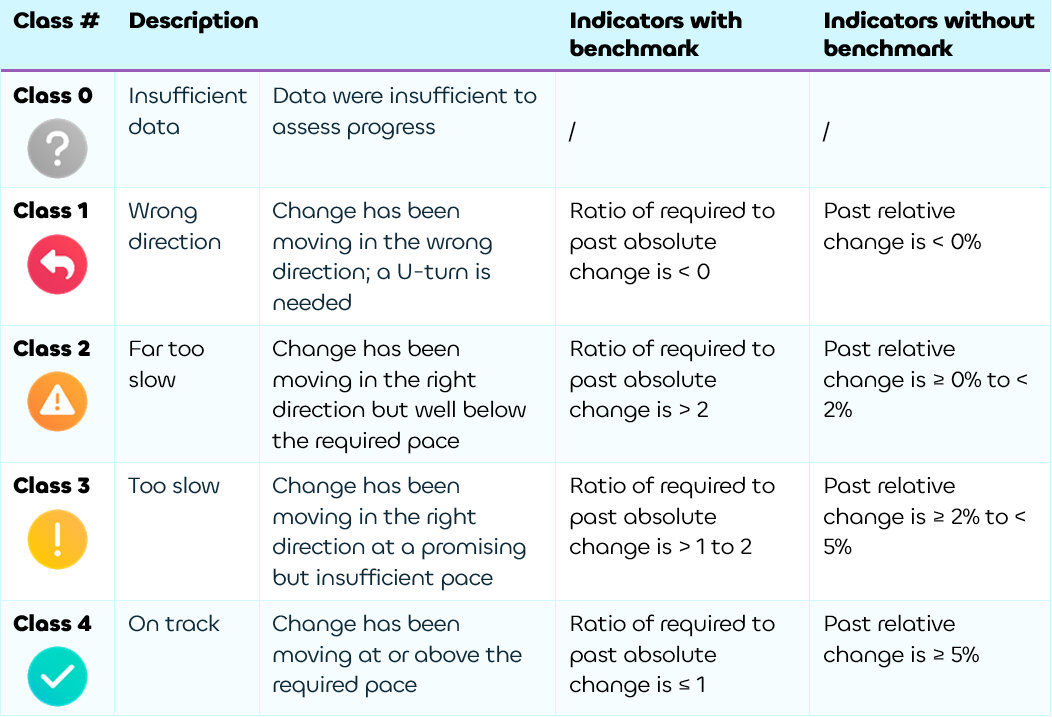

Classification

Progress for each indicator is classified as either: on track, too slow, far too slow, or headed in the wrong direction. Insufficient data indicates data availability limitations.

For indicators with a defined benchmark the classification is based on the ratio of the required change to the past observed change. For indicators without a defined benchmark this is based on the desired direction and speed of change using predefined ranges. However, the assessment may deviate from the given ranges to reflect on the characteristics of an indicator.

The same system is used to describe overall progress in each building block. This assessment is based on expert judgement informed by a nuanced reflection on the indicator values, their respective importance, and recent developments in the policy area in the context of past trends.