Glossary

Glossary

OVERVIEW:

Progress on buildings has been far too slow

There is no sign of improvements in the latest data and there has been only limited policy action since. Particularly building renovation needs to progress faster, using national incentive schemes.

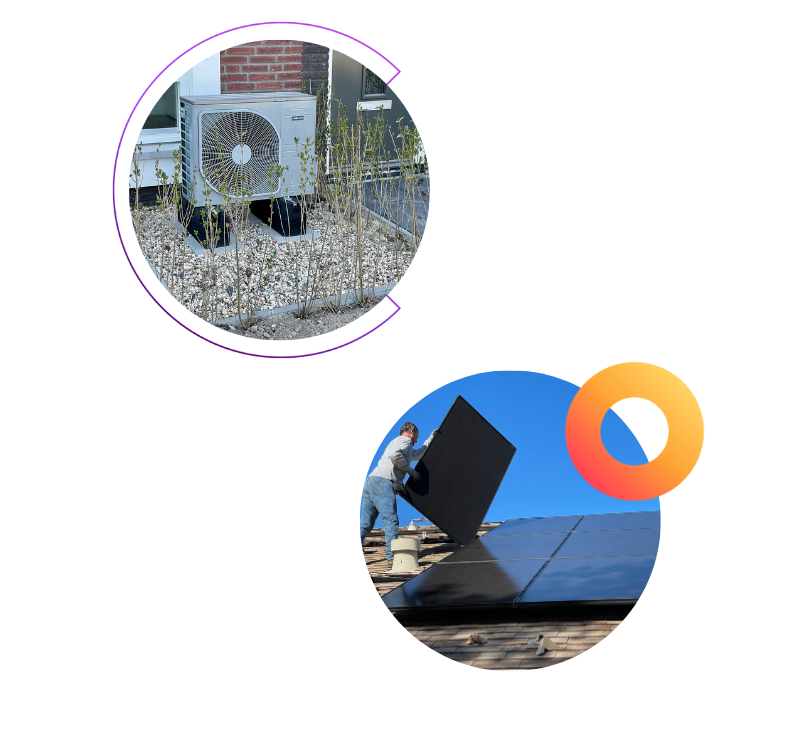

Progress towards climate neutrality in the buildings sector was far too slow – the same as last year’s assessment. This is primarily due to operational emissions from buildings, which are not declining rapidly enough to reach the EU’s 2030 targets. Current renovation rates, especially for deep renovation, are insufficient. In the assessed period, heating energy demand was only slightly decreasing but not sufficiently to reach EU targets for 2030. Additionally, the current transition to renewable energy in buildings is not sufficient to significantly lower emissions. Despite a notable increase in heat pump sales in the EU since 2016, this trend decreased in 2023. While in principle, a fair reduction in the average space per person is the most efficient way to lower emissions, the recent trend shows an increase.

In 2023, there were significant changes in policy with revisions to three main directives: Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), Energy Efficiency Directive (EED), Renewable Energy Directive (RED). While most of the indicators in this assessment are covered by these directives, it is too early to gauge their impact. The latest version of the EPBD is a compromise: it delays and reduces the ambition for Zero-Emission Buildings (ZEB) and Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) compared to the EC proposal. However, it still outlines a clear plan for non-residential buildings with MEPS and establishes an energy efficiency trajectory for residential buildings. It also includes provisions to simplify the energy renovation process, e.g., by defining deep renovations and improving access to information and financing renovations.

Action to reduce operational emissions is insufficient and should primarily focus on shifting to renewable energy, particularly through the accelerated deployment of heat pumps. For renovations, an enforcement system should accompany MEPS to monitor their deployment and impacts effectively. Additionally, providing grants through public finance would address the financial barriers faced by low-income and vulnerable households, as well as rental households. Thirdly, establishing national databases for building energy performance is a crucial step to address the lack of centralised, comparable, and up-to-date data. Finally, a reduction target should be set for all embodied emissions, including renovations, such as broadening the definition of ZEB to encompass lifecycle carbon.

OBJECTIVES

Objectives describe what needs to be achieved in each building block to reach climate neutrality.

Objective

Reducing buildings emissions and limiting material demand

The EU fell short of its target to cut buildings’ GHG by 60% by 2030 compared to 2015 levels. To meet the target, emissions reductions in the buildings sector need to more than triple from 2023 to 2030. Constructing buildings and related works in the EU accounted for 9.4% of all domestic GHG emissions in 2019. Improved material efficiency could potentially reduce 80% of these emissions. However, the demand for cement or concrete blocks and bricks increased by an average of 7% annually between 2017 and 2022.

GHG emissions from buildings

The data shows past progress of 9,3 Mt CO2e between 2017 and 2022. The target is a 60% reduction of buildings GHG emissions between 2015 and 2030. To meet the target, the required annual change between 2023 and 2030 need to be 3.6 times faster than the past rate of progress.

Buildings direct emissions are the aggregate GHG emissions of the category commercial/institutional and residential buildings. Those emissions do not capture the indirect emissions (electricity and energy production) nor the embedded emissions of buildings material.

Demand of cement or concrete blocks and bricks

The Demand of cement or concrete blocks and bricks increased by 7.1% per year (trendline) between 2017 and 2022. Although there is no target on this indicator, this increasing trend is not aligned with the need for decreasing material demand for new buildings floor area, and their related embodied emissions.

The production, import and export at the EU level of building blocks and bricks of cement or concrete is published by Eurostat. The demand for building blocks and bricks is approximated by summing the annual production and the imports minus the exports.

ENABLERS

Enablers are the supporting conditions and underlying changes needed to meet the objectives in a given building block. They are the opposite of barriers or inhibitors.

Enabler 1

Reducing demand for heating and cooling

The trend for reducing the surface area of buildings, which reduces energy demand, was heading in the wrong direction between 2015 and 2020. The limited decrease in energy consumption for heating and cooling indicates insufficient progress towards achieving the Renovation Wave target of an 18% reduction by 2030 compared to 2015 levels. However, the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions could have affected this indicator in 2020 and 2021. With individuals spending more time at home, it might have resulted in a less significant decrease in the trend.

Average space per capita

The average space per capita increased by 0.8 m²/capita per year between 2015 and 2020. Although there is no target on this indicator, the growing historical trend is not aligned with the need to reduce heating and cooling services.

The average space per capita is the ratio between the total surface of buildings (residential and services) and the population.

Demand for heating and cooling

The annual decrease of the final energy consumption for heating and cooling between 2010 and 2015 was 1.5 kWh/m2. Given the age of the data, this indicator is supplemented by another with more recent data but a reduced scope (heating only).

The average final energy consumption for space heating and cooling is obtained by dividing the total consumption for space heating and cooling by the total buildings area. Final energy consumption for space heating (resp. cooling) is normalized with the heating degree days (resp. cooling degree days) to smooth out climate variability.

Demand for heating of residential buildings

The annual decreases of the final energy consumption of households for heating was 0.3 kWh/m² per year between 2016 and 2021. This indicates insufficient progress towards achieving the Renovation Wave target of an 18% reduction by 2030 compared to 2015 levels.

The indicator measures the final energy consumption per m² of households for space heating. The final energy consumption is scaled to EU average climate to smooth out climate variability.

Enabler 2

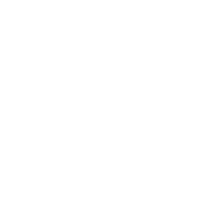

Facilitating the renovation of buildings

Data on EU renovations are sparse, hindering implementation tracking. The renovation rate needs to double by 2030 to reach the EU target. Renovation rates of 0.2% for residential and 0.3% for non-residential buildings indicate a lack of common deep renovation practices. Since the publication of these figures, the revised EPBD has refined the renovation level needed to achieve deep renovation. Annual investments in renovation increased by 5% per year between 2012 and 2016, or 13 billion EUR per year. Despite the lack of recent data, renovation rates and depth are considered far too slow to achieve the goals of the Renovation Wave, as are investments.

Investments for energy renovation

The annual investments in renovation increased by 5% or 13.2 billion EUR per year between 2012 and 2016 which is going in the right direction, however far too slow.

The average annual energy-related investments in renovation covers both the private and public investments.

Average renovation rate

There is not enough data to derive a trend but the average renovation rate was estimated close to 1% in for the period 2012-2016. To reach the 2030 target of 2-3%, the rate has to double.

As renovation depths are classified based on achieved primary energy savings, the average (or weighted) renovation rate describes the annual reduction of primary energy consumption achieved through the sum of energy renovations of all depths.

Deep renovation rate of residential buildings

There is not enough data to derive a trend but the average annual amount of deep renovation of residential buildings for the period 2012-2016 was only around 0.2%. This indicates a lack of common deep renovation practices.

This indicator measures the rate of renovations with primary energy savings above 60% of residential buildings.

Deep renovation rate of non-residential buildings

There is not enough data to derive a trend but the average annual amount of deep renovation of non-residential buildings for the period 2012-2016 was only around 0.3%. This indicates a lack of common deep renovation practices.

This indicator measures the rate of renovations with primary energy savings above 60% of non-residential buildings.

Enabler 3

Accelerate the technology switch

Progress in decarbonising heat supply was sluggish, with data indicating an annual increase of renewable energy in heating and cooling of only 0.7% between 2017 and 2022, mostly due to the contribution of biomass and heat pumps. The sale of heat pumps saw significant growth. Recent data however suggest that this trend decreased in 2023. An accelerated trajectory is essential to achieve the target of a 60 million heat pump stock by 2030, as suggested by the impact assessment on the 2040 climate target.

Share of renewable energy in heating and cooling

Data show an annual increase of 0.7%-points between 2017 and 2022 which is far too slow to reach 100% for phasing-out fossil fuels by 2040. The required annual change between 2022 and 2030 needs to increase to 3%-points which is 4 times faster than the current rate of progress.

The share of renewable energy used for heating and cooling includes solar thermal, geothermal energy, ambient heat captured by heat pumps, solid, liquid, and gaseous biofuels, and the renewable part of waste.

Heat pump sales

The sale of heat pumps has seen significant growth from 2016 to 2021, resulting in an average annual increase of 0.2 million in sales of units. Recent data however suggests that this trend has decreased in 2023.

Annual sales of heat pumps in EU-27. The indicator focuses on heat pumps for heating.